A grim joke from Soviet times: A Soviet citizen is thrown into jail. “How long is your sentence?” he is asked by his cell mates. “Ten years,” he replies. “For what?” ask the cellmates. “For nothing,” he says. “You liar!” say the cellmates. “They only give five for nothing!”

Vladimir Putin and Russia’s ruling elite probably hoped that Alexei Navalny, a fierce critic, and exposer of the regime’s rampant corruption, would remain in Germany, dead or alive.

But Navalny survived the attempt on his life with a nerve agent from the Novichok family and had no choice but to go back to Russia. He is the Kremlin’s only remaining prominent domestic adversary. The rest have been exiled or killed. For millions of Russians, he represents the hope that there is an alternative to Putin’s regime. That free and fair elections, a free media, independent courts, and the eradication of corruption might soon be possible in Russia. In returning to Moscow, Navalny let down neither his supporters nor his country.

At the Sheremetyevo airport, right before he was taken to a police station in Khimki in the outskirts of Moscow, Navalny said that he was not afraid. This probably horrified the Kremlin, as the Russian authorities themselves seem scared. Just as in Soviet times, the leaders fear a group of people—Navalny and those close supporters who have now also been arrested—because they rightly guess that there are millions of others behind them. People who are daily served state propaganda but are fed up with the state’s undelivered promises and their own worsening living conditions.

Russia’s Parody of the Rule of Law

In a grotesque parody of the rule of law, the police station in Khimki was hurriedly transformed into a ‘courthouse’, filled with what appeared to be policemen dressed in civilian clothes, imitating a public court session. A regime that fakes elections and totally distorts democracy cannot respect the law. The only part of the charade that did follow the law—the act of letting Navalny, a Russian citizen, enter Russia—was a necessity forced upon the Russian authorities, who had no other choice.

Navalny will most likely be sent to prison for several years, perhaps as many as 13.5, on fabricated charges. Putin wants Navalny and his closest associates locked away and silenced for as long as possible. However, while it pretends indifference, Russia’s foremost fear is probably international reaction, particularly from Germany, the place of Navalny’s hospitalization and physical rehabilitation, and by far the most important European country for Russia’s political and economic interests, including the completion of Nord Stream 2. But Germany now also has a moral attachment to and responsibility for Navalny’s fate.

Mass Protests à la Belarus

There will certainly be headlines in the international media when Navalny is sentenced. The Kremlin will do its utmost to see that such headlines disappear and that interest in Navalny fades. Moscow might attempt to trade him, for example relocating him to Germany, as a gesture of ‘good will’ in exchange for the completion of Nord Stream 2.

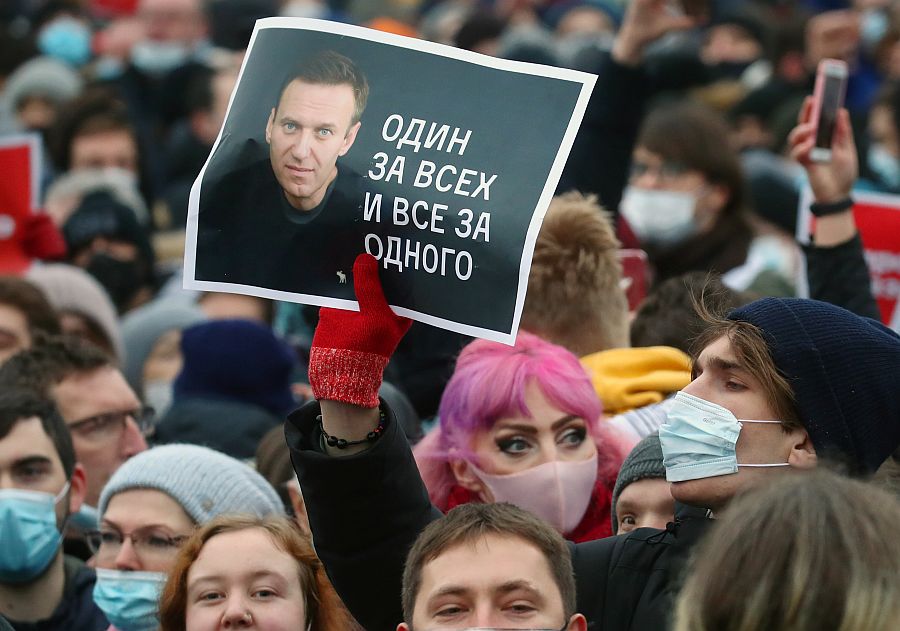

Thousands of demonstrators who demanded Navalny’s release, fired up by his recent exposure of the huge estate in the vicinity of the resort town of Gelendzhik that he attributes to Putin, were arrested all over Russia on 23 January. The Kremlin has already demonstrated its intentions and methods through its support, since August 2020, to Alexander Lukashenko’s regime in Belarus. Putin is likely determined to apply the same approach—a war of attrition against the opposition, until mass protests ultimately cease. The Kremlin understands only zero-sum games, including domestically. It cannot bend. The people must submit.

Navalny Has Two Faces

Nevertheless, it should not be forgotten that Navalny, Russia’s foremost fighter against corruption, has a second face. He wholeheartedly supported Russia’s aggression against Georgia, in 2008, and the illegal occupation and annexation of Crimea, in 2014. At least a few years ago, he favoured a rather nationalistic, even racist approach to Caucasians and others.

It remains to be seen whether the Navalny case will mark a turning point for the West’s relations with Russia, or for Russia itself. But in their dealings with Russia, as with their consideration of Navalny, Western countries must be wary of straightforward judgements.

Views expressed in ICDS publications are those of the author(s).